Headquarters: Svetog Nauma 7, 11000

Office address: Đorđa Vajferta 13, 11000

Phone:: +381 11 4529 323

In the context of reinforcement of the EU’s strategic autonomy, the first part of the triptych blog was mainly dedicated to the war in Ukraine and its respective challenges, whereas the second investigated the transatlantic relationship. However, in the years to come, among crucial things for the EU will be to position itself as regards the rise of China and the proliferation of ‘regional powers’ that occupy a middle-level position in the international power spectrum, project significant influence, and reveal some capacity to shape international developments, especially in the closest EU neighbourhood. In an ever more fragmented world characterised by an increasingly transactional approach to foreign policy and a myriad of interdependencies the EU has with different countries, the EU ought to prepare for political coexistence and competition and privilege de-risking over decoupling. In light of such a frame of reference, the third part of the blog will analyse how the concept of the EU’s strategic autonomy could manifest itself in a relationship with China, Turkey, and countries of the Middle Eastern region.

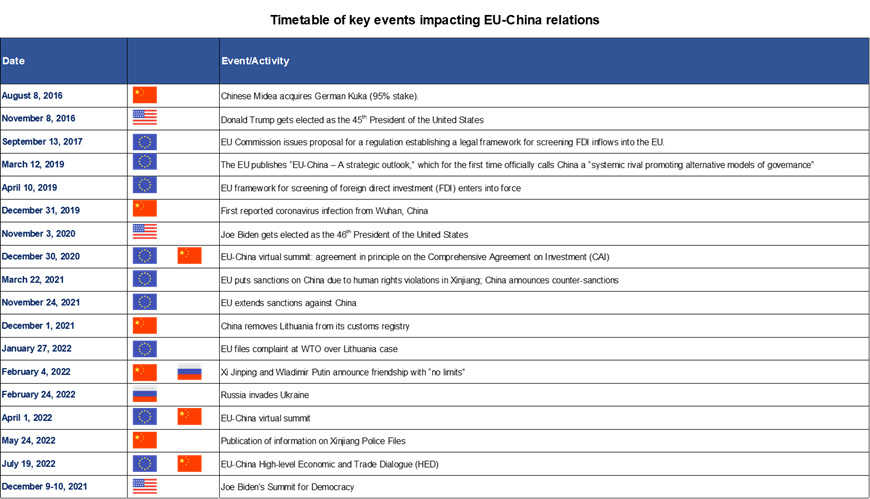

In the years behind us, Sino–European relations have undergone dramatic changes. China’s integration into global value chains after its 2001 WTO accession led to increasing interdependence with the EU. The Kuka takeover in the mid-2010s, as part of the hunt for German future-orientated industry champions, marked a turning point for rethinking at the political level consequences of cooperation with China. Thus, in 2019, the EU Commission launched an EU-wide FDI screening mechanism, and from there, it just unwound. In 2021, the EU, for the first time in 30 years, sanctioned China for the systematic violation of human rights in Xinjiang province, whereas China, in a tit-for-tat reaction, immediately imposed countersanctions, targeting, for example, members of the European Parliament. Subsequently, China decided to teach Lithuania a strong economic lesson by applying discriminatory and coercive measures against exports from Lithuania and against exports of EU products containing Lithuanian content after Taiwan officially opened a new representative office in Vilnius and dubbed it “Taiwanese Representative Office in Vilnius”, ultimately resulting in a WTO dispute. Finally, reimagined China’s and Russia’s “no limits” friendship and subsequent China’s lukewarm support of Russia’s war in Ukraine seem to be among the final nails in the coffin of the strategic partnership between the EU and China.

Table 1: Timetable of key events impacting EU China relations. See more at this link.

While the EU labelled the next phase of EU-China relations as a dynamic blend of partnership, competition, and systemic rivalry, the future is poised to usher in a captivating era of divergence and a deliberate shift towards the greater distance. In most cases, EU countries’ political elites view the world as undergoing a polarisation between democracies committed to rules and revisionist autocracies, with swing states positioned in between. As much as this might also be the case, the main axis of global polarisation is arguably centred around different outlooks on desirable underlying premisses of the international order and, more importantly, the exclusive or non-exclusive right to set governing arrangements among states. This does not mean that the EU necessarily needs to be involved in each story in which, for reasons of geography and capacity, the United States is likely to have the principal role. Realistically, the EU has no substantial means to project its soft power on China, whereas the use of hard power is out of the equation. Therefore, the game of “disciplining” China might be the one where the EU could call in sick. Instead, it should strive to fully enforce its open regulatory standards towards Chinese entities, thus showing its capacity to impose the norms in its bilateral relations and clearly demonstrate to any stakeholder that “Europe is a player, not a playing field”, yet a player with no intention to prescribe rules of all other bilateral relations across the globe.

Türkiye is in a customs union with the EU and has been a candidate for accession since 1995, however, the relationship between Türkiye and the EU has been on a path of decline in the last decade. In 2019, the European Parliament called for the suspension of full membership negotiations between the EU and Turkey, and the newest European Parliament’s report in 2023 heavily criticised Turkey as well. In turn, this sparked President’s Erdogan threats that it will seriously consider “parting ways” with the EU. Therefore, the EU’s relationship with Turkey is stuck at an impasse. EU policymakers can no longer conduct effective diplomacy or formulate a wider geopolitical strategy premised on Turkey acceding to the union.

As the prospects of Turkey’s accession to the EU diminished completely, there is a dire need for reconceptualising the relationship between these two geopolitical players. The reconceptualisation must consider two, what now seem to be, facts. First, the EU’s conditionality is hardly going to stop democratic backsliding in Turkey. Second, Turkey’s accession process is in a gridlock that will hardly be resolved any time soon. Therefore, the most reasonable thing to do would be to adopt a more transactional approach to cooperation. This would include deepening the customs union, which is a part of the association agreement with Turkey (Ankara agreement), whereas “tools like high-level political dialogue, people-to-people contacts, Turkey’s participation in select EU programs and its use of EU funds, and the issue of visa liberalisation would also be on the table”. On the other hand, with violent flare-ups between Serbs and Albanians in the northern part of Kosovo*, the recent turn of events in Nagorno-Karabakh, the de-facto state of war between Israel and Hamas, as well as the war in Ukraine, EU’s extended neighbourhood has stepped on a chaotic path of geopolitical turmoil. In such circumstances and given how Turkey exploited its strategic location to play a decisive role in some of these conflicts, Europe will need to come up with imaginative diplomacy to more deeply engage Turkey given its increasing geostrategic importance.

Should one possess no prior acquaintance with the complex tapestry of politics and geopolitics, and should they be granted an introduction to the proximity of the EU to the Middle East, the intricate web of migration politics, the daunting implications of Islamic terrorism, and the pivotal access to energy resources in the wake of decoupling with Russia, their natural inclination might lead them to envision the EU as the preeminent external figure in the Middle Eastern narrative. The revelation that the EU wields considerably less influence in the region would then evoke quite a surprise.

For a long period of time, the EU has been attempting to play geopolitics relying solely on values and technocratic EU rules and standards. After Gaddafi’s removal in 2011, the EU extended offers to new governments in the form of Euro-Mediterranean Partnership and ENP participation, along with incentives. Similar plans were proposed to Algeria and Egypt, but in all instances, the regimes either rejected EU cooperation or accepted funds while resisting its cooperative security norms. However, things have arguably started to change recently. For example, in 2023, bin Salman was in Paris, where he was greeted with more than a cordial handshake with Macron at the Élysée presidential palace less than five years after Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi was killed and dismembered in Saudi Arabia’s consulate in Istanbul. Such diplomatic actions of one of the most important EU members might signal the EU’s shift to geopolitics based on realpolitik principles. However, the re-emergence of the EU’s stability-oriented security policy leads to: compromises in the promotion of democracy and human rights; perceived U.S. and European double standards in the promotion of values; a crisis of the so-called liberal alliance.

What this means is that the EU is being closed in between two tough choices in the Middle East – playing the realpolitik card and being called out for hypocrisy for cooperating with illiberal/autocratic countries with no strings attached on the one side and pushing through value-preconditioned geopolitical agenda on the other. Given the current state of affairs, the EU should opt for the former scenario for several reasons. Firstly, since the Arab Spring, the Middle East has witnessed the increasing interference of many relevant geopolitical actors who are willing to offer a lot. This proliferation of actors further complicates the EU’s conditioning policies. Secondly, bandwagoning with the United States may lead to the dominant ally ignoring the EU’s vital security concerns in favour of other geopolitical priorities. Thirdly, the majority of the contemporary Middle East is now on a path towards solidification of the power of brutal, illegitimate, and authoritarian regimes. This will make it strenuous for the EU to cooperate selectively with some and not with others (e.g., Saudi Arabia and Iran) while simultaneously retaining its veil of integrity and trustworthiness. Instead, the EU needs to adapt to the region, rather than seeking to adapt the region to its own value prisms, and at the same time clearly signal to Middle Eastern partners that externally, its geopolitical and security interests come as a priority, whereas as its values are not to be challenged internally.

In summary, the EU should not define itself in opposition to or in league with China, but instead, provide itself with a foreign policy framework that would allow cooperation and competition with China based on a clear understanding of each other’s interests. As regards Turkey and many Middle Eastern countries, such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, the EU should pursue transactional relationships. As most of these countries seek to escape the United States’ grip and become entangled in great power competition, this opens the space for the EU to impose itself as a relevant geopolitical player with whom these countries can cooperate without being driven into what they consider a hypocritical global war in defence of one or the other global order. While it should privilege relationships with partners that share its values, the EU will need to coexist, and sometimes work, with other countries, too. Its geopolitical future will thus depend on the ability to protect its values internally with the powers that seek to challenge them, but on the outside, the EU will need to protect primarily its interests and not values. In other words: “Rather than making the world safe for democracy, the goal should be to make European democracies safe in the world”.

This is the third and the final part of the blog, you can read the first part here and the second part here.