Headquarters: Svetog Nauma 7, 11000

Office address: Đorđa Vajferta 13, 11000

Phone:: +381 11 4529 323

TABLE OF CONTENT

With consequential geopolitical shifts and fractures that will hardly heal any time soon, overt pressure combined with subtler influence to conform to new norms of international relations seemingly started to structure the overall relationship on a global level. The inability to conform to these norms now might come in a package with visible consequences. In the period of the imposed reestablishment of the politics of bipolarity and the “Cold War 2.0” mindset, there is little chance that occupying a position beyond the limitations of a patron-client relationship will be possible at all.

A quick screening of the transatlantic relationship between the United States and the European Union might convince us that we are precisely where we were twenty or forty years ago – trade-related disputes and different perspectives to applying tact in diplomatic endeavours and international diplomacy as the only sources of tensions in otherwise flawless compatibility. However, after a decade or two of dancing on the wire and following the path that ends up in an impasse, where several power centres balance each other out, global powers, including the US, seem to have lost their patience. Rather than sharing responsibilities and power, now there is only room for sharing liabilities. After decades of strategic partnership between the US and the EU, it seems that “Cold War 2.0” might move the relationship closer to American dominance and European dependency. The agency of the Three Seas Initiative, Open Balkans, and overreliance on NATO might be crucial aspects of such reinvented relationship. The only foot-in-the-door is arguably the concept of common European defence hand-in-hand with more robust geopolitical autonomy and more vital positioning in neighbouring regions.

The Intermarium, or in other words, the geographical space between the Baltic Sea, the Black Sea, and the Adriatic Sea, has always been a recreation ground for various empires to test their political, economic, and military strengths, exercise their power, and test the limits of their strategic depth. We are now observing the contemporary revival of the Intermarium geopolitical project through newly emerged formats of Three Seas Initiatives (TSI) and Bucharest Nine (B9). In the modern world, this geopolitical concept was first used as a metaphor for the containment and isolation of [1] – Germany and Russia in post-World War I Europe. However, even the Intermarium as a sort of a conceptual predecessor to TSI has its conceptual forerunner used by Sir Halford Mackinder at the Versailles Conference – cordon sanitaire, the buffer belt zone consisting of smaller democratic states that narrow down the risk of closer cooperation between Germany and Russia. Following the pessimistic maxim of Rust Cohle from the popular TV series ‘True Detective’ – “time is a flat circle”, we might be witnessing yet another revitalisation of a century-old geopolitical concept.

Officially, the TSI and B9 initiatives are to be perceived as complementary, not in competition, with the EU. However, the question remains whether this perception truly reflects the dynamics at play. The focus of both initiatives lies primarily on expanding North-South infrastructure with little thought of the European East-West axis. Moreover, TSI itself is, in fact, a follow-on from the “North-South Corridor” project in 2014 led by the Atlantic Council, an organisation with the official mission to galvanise US global leadership. Moving along on the timeline, in 2017, former US President Trump endorsed the project while taking part in the Warsaw summit, thus throwing his weight behind the TSI and helping Poland to “resurrect a pre-World War II Polish plan […] to unite Central and Eastern Europe under Polish leadership and then counterbalance German leadership to the west and Russia to the east and […] drive a wedge between “new” and “old” Europe, reprising the strategy pursued by then-Secretary of Defence, Donald Rumsfeld, in the run-up to the Iraq War of 2003.” Optimistic EU decision-makers seem to have waited for the ‘Trump threat’ to pass and expected everything to go back to as it once was after seeing Trump off. However, NATO’s centre of gravity seems to continue shifting away from the Franco-German tandem to eastern flank countries at a steady pace, thus reinvigorating another power axis within the EU. Although this might contribute to further democratisation of decision-making processes within the EU, it could as much create a rift between two potential blocs asking respectively for a more geopolitical autonomy of the EU and requesting further alignment with US policies and geopolitical intentions.

Yet another interesting initiative comes from the Western Balkan – the ‘Open Balkan’, before the Economic Forum on Regional Cooperation held in Skopje in 2021, also known as ‘Mini-Schengen’. Formally pioneered by Serbia, Albania, and North Macedonia, yet, given the United States’ exceptional support of the initiative, sceptics would say that it was, in fact, conceived by the United States to take advantage of the limited ability of the EU to smooth out the differences between ‘old’ and ‘new/potential’ member states. Some experts claim that the initiative unnecessarily duplicates the Common Regional Market (CRM) prospects, which have arisen under the auspices of the Berlin process, where the EU and especially Germany, have much greater authority. Some even identify “dangerous implications” that the initiative might have for the region due to risks of making existing political problems worse despite the dubious nature of such views. Proponents of the initiative insist on positive aspects of increased trade and cooperation but sometimes focus narrowly on Open Balkan’s potential to build on the CRM legacy as if the WB countries could not have done the same through the CRM. Perhaps, that is why the EU’s envoy for Belgrade-Pristina dialogue, Miroslav Lajcak, described the initiative as “unhealthy competition” with the EU integration process. A strong transatlantic link inherent to the Open Balkans thus might tilt the balance in favour of the transatlantic integration process (at the expense of the increasingly uncertain EU integration process) with a focus on the same sectors – energy, transport, and digital sectors, as in its previously discussed counterpart initiative – TSI.

Several other occurrences also indicate the growing influence of the US in the region at the expense of the EU. Until recently, prior to the Franco-German proposal for the normalisation of relations between Belgrade and Pristina, and apart from the growing number of ethnically motivated incidents and violence against Serbs, the Belgrade-Pristina dialogue and situation on the ground remained in a stalemate. Initially, Trump’s administration kickstarted parallel US-led talks, overshadowing European efforts and monopolising the mediation role. However, with Joe Biden’s presidency and appointment of two seasoned diplomats with relevant experience – Christopher Hill in Belgrade and Jeffrey Hovenier in Pristina, seemingly, the EU-facilitated process got reinvigorated. Yet, even such a turn of events left analysts with an aftertaste that the US interference and dominance even over the EU-led dialogue process is inevitable.

Besides the US’ increased involvement in the Belgrade-Pristina dialogue, there are other regional affairs in which the US aim to play a more active and dominant role. For example, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the US and UK strongly supported sudden changes to Bosnia’s election law made by the peace envoy Christian Schmidt minutes after most polling stations closed last year. In contrast, EU countries might not have been particularly satisfied, according to some commentaries and the fact that most EU and EU member countries’ representatives remained mute. Eventually, Schmidt was even requested to appear before the Foreign Affairs Committee of the European Parliament to “clarify the reasons for such undemocratic measures”. Similarly, in 2021, when Serbian leader Dodik was, like countless times before, threatening to create a breakaway ethnic-Serb army and withdraw Bosnian Serbs from central institutions, it was Gabriel Escobar, a high-level US diplomat, who met with Dodik and deescalated the situation. Therefore, should the EU wish to preserve its diplomatic dominance over the region, it must also be aware that sending clear and strong signals about its leading diplomatic and mediation role in the region is of the utmost importance.

Theoretically, the EU strategic autonomy is inseparably intertwined with the security realm, but in practice, the idea of EU military independence has never managed to grow out of NATO’s shadow. Now ancient history – in 2019, Macron announced to the world that NATO is “brain dead”. Shortly after that, in 2021, France and Greece signed a landmark military agreement that provides mutual assistance in the event of one party coming under attack by a third country, even if the latter belongs to NATO. Many saw this as the first step towards the so-called ‘European army’ that has already been incorporated into the European People’s Party programme, set out in Madrid in 2015, and the programme of Emmanuel Macron’s La République En Marche. All the political proponents of the independent EU armed forces, such as Angela Merkel or Jean-Claude Juncker, now seem far away from the stage lights, whereas Macron, according to the new Czech president, made a “reasonable shift”. In the aftermath of the discomforting Australia’s surprise decision to scrap a huge submarine deal with France in favour of nuclear-powered subs from the US and Britain, the idea of the EU army turned out to be only “a midsummer night’s dream” of Macron.

Vis-à-vis the EU’s strategic autonomy, the brave albeit light-hearted idea of the European army does not just sound complimentary but also necessary. However, in the current context of the war in Ukraine and consequential NATO revival, pursuing the idea of the EU army is unrealistic for numerous reasons, but that does not exclude further relevant reforms. First, to enable the most basic ability to defend itself as a political unit, the EU should develop a Rapid Deployment Capacity (EU RDC) consisting of up to 5.000 troops as quickly as possible. As the case of the Afghan government collapse demonstrated, the possibility for rapid response and determined troop deployment is of utmost importance for guaranteeing the security of its citizens abroad.

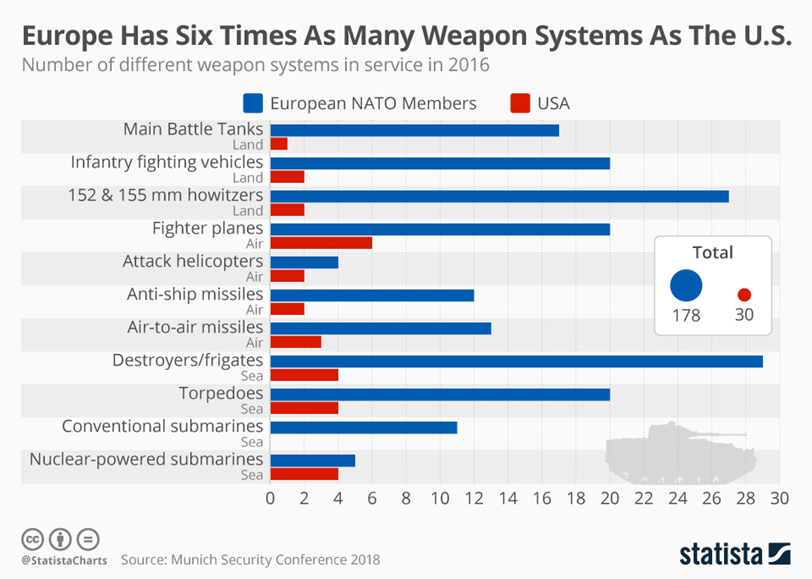

Secondly, the efficiency of EU member states’ militaries is extraordinarily low, given that the EU as a whole, even in 2016, had six times as many weapon systems in service as the U.S., including 17 different types of main battle tanks and 27 different howitzers (Graph 1). Increasing efficiency is thus not only the EU countries’ priority but should be the priority of NATO as well as no one can afford to have all EU members planning, developing or procuring in isolation. Therefore, the existing Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) framework, especially commitments related to bringing their defence apparatus into line with each other, should be propped up by both EU and NATO to improve the interoperability of forces and develop joint defence capabilities of EU countries.

Chart 1: Number of different weapons systems in service in 2016

Source: Statista

Thirdly, as much as Article 5 of NATO’s Washington Treaty (the principle of collective defence) might be more renowned, the Article 42(7) Treaty on European Union has a much ‘more compelling nature’, given the explicit obligation of the EU Member States to come to the defence of the victim state, and that they have to do so by ‘all the means’ in their power, not just the means they think are necessary. Article 42 TEU sets a clear objective that ‘Union defence policy […] will lead to a common defence’, which might be interpreted even as an obligation – to think about the form the common defence should take and how it should be realised. Therefore, regarding the greater military autonomy, the EU has a well-defined starting point and a path to pursue, normative grounds to call upon, and compatibility and shared interest with NATO to count on.

In summary, the Three Seas Initiative and Open Balkans are two significant US-driven geopolitical initiatives in Europe with the intention of reducing regions’ dependence on unwanted external actors. To have them promote a more united and prosperous Europe in addition to boosting economic, energy, and security cooperation between the participating countries, the EU administration, including France and Germany, need to step up and do more to put these two projects under its auspices. Europe faces several geopolitical challenges simultaneously, and the US’s precipitate withdrawal from Afghanistan demonstrated the continued intention of the US to act in its own interests first. Altogether, Europe is thus required to enhance its security and autonomous defence capacities and assert its position as a global actor. To do so, establishing an EU army might still be a far-fetched idea, yet the EU has an established path to pursue that requires minimal consensus and resources – proceed with EU Rapid Deployment Capacity development and improvement of interoperability of forces and joint defence capabilities.

You can view the first part of this blog here.

The final third part of the blog series will study the relationship with other geopolitical competitors, respectively, in the context of opportunities for achieving deeper EU-SA.

[1] Stanley F. Gilchrist, ‘The Cordon Sanitaire—Is It Useful? Is It Practical?’, Naval War College Review 35, no. 3 (1982): 60–72.

[2] See more about this in a letter signed by a broad coalition of over 25 25 representatives from the European, German, Dutch and French Parliaments at the following link.