Headquarters: Svetog Nauma 7, 11000

Office address: Đorđa Vajferta 13, 11000

Phone:: +381 11 4529 323

If the 2007 Munich Vladimir Putin’s speech, the financial and economic crash of 2008, and the rise of China as a most apparent geopolitical challenger and potential superpower have not been sufficiently indicative for some, the last few years brought more perplexities. The COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitically premised reconstruction of global supply chains, the US’s abrupt withdrawal from Afghanistan, the war in Ukraine, regional forces starting to reject a world order dominated only by several international players, be they from the West or the East… It seems that no longer will anyone be able to sit tight and watch the geopolitical arrows fly overhead between Washington DC, Beijing, and Moscow as, unlike in the Cold War, the politics of non-alignment will not be tolerated.

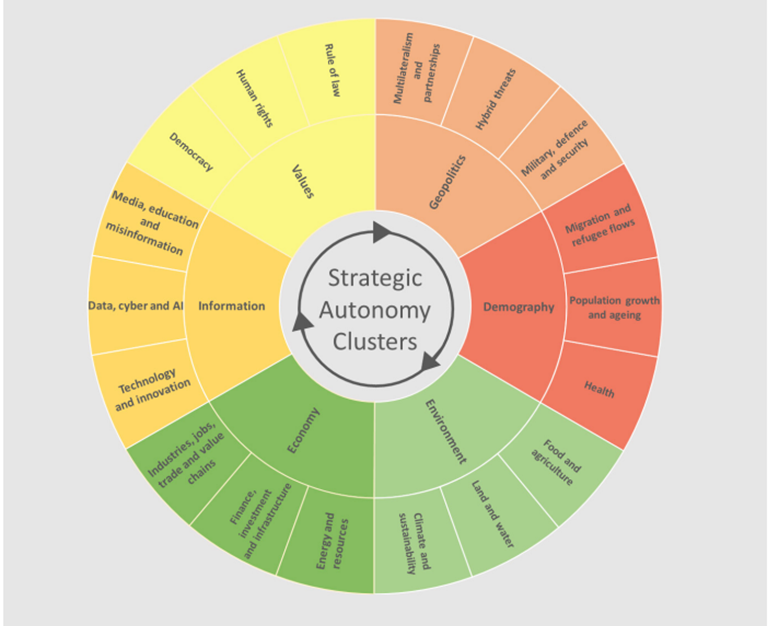

With the geopolitical realignments underway, and some just waiting to emerge, Europe will have to dig out the old textbooks it wrote long ago and remind itself how geopolitics is being played. In other words, the EU might be on the verge of ending up in the geopolitical backwater unless it starts making sound strategic geopolitical moves autonomously. Obviously, the word choice, including “strategic” and “autonomously”, has been intentional, as this paper argues that the strategic autonomy concept is an appropriate framework at the outset. However, for it to yield results, some other complementary political and geopolitical shifts need to be made. An approach is necessary that goes beyond merely listing a standard menu of policy areas and saying the EU needs more capacity in each of them. An approach is necessary that perceives power beyond hardware-type quantitative indicators, which is a low-key approach compared to geopolitical needs and ambitions that the EU has or should have.[1]See more at: https://carnegieeurope.eu/2021/03/08/eu-s-strategic-autonomy-trap-pub-83955. To respond to the problem raised, this part of the blog series will examine the war in Ukraine and respective challenges linked with the EU’s diplomatic power and influence, economic resilience, and energy (in)dependence.

The broader impact of the war in Ukraine, the third asymmetric shock that the Union has experienced in the last two decades after the Eurozone crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, exposed how much work is left on increasing the influence of EU diplomacy, bolstering European economic resilience, and reducing energy dependence. The most notable diplomatic effort to avoid the current conflict was that of the “Normandy Four” format, which included the Franco-German EU engine on the mediator side and Russia and Ukraine as interested parties. The accords sought to halt the armed conflict in eastern Ukraine in 2014. Unfortunately, both Minsk and Minsk II peace agreements failed to deliver any results whatsoever. Although the conflict got reduced to limited trench warfare for an extended time and arguably saved many lives yet, at the same time, it was evident that the two sides wanted diametrically opposed outcomes and that agreements left too much space for both sides to argue for interpretations that are advantageous to them.[2]

Europe obviously could not have chosen to be reticent in the context of its immediate backyard being on fire. Yet, failures of both the Minsk and Minsk II agreements brought diplomatic reputational damage to the EU. Macron’s statements from February 2022 about Putin’s true strategic ambitions[3] convince us that Europe did not misconstrue and curtail the conflict that it voluntarily applied to solve. However, in that case, the question remains – if the Europeans recognised the Ukrainian crisis as much more than Ukraine itself, why did not their mediation platform immediately pursue a wider and more strategic agenda that could address the true nature that drove this particular standoff – a clash in the worldviews of Russia and the West over the entire security architecture of Europe.[4] Instead, the EU opted for mediation efforts within the narrow Minsk agreements framework that were obviously going to prove futile, given its reductive ‘ceasefire instrument’ nature. Hence, should the EU aspire to (re)impose itself as a diplomatic power, it needs to engage in a more careful critical pre-assessment of the level of success of its future diplomatic initiatives and start thinking on how to go beyond the “we are concerned” approach by evaluating all tools at its disposal, including hard-power foreign policy influence.

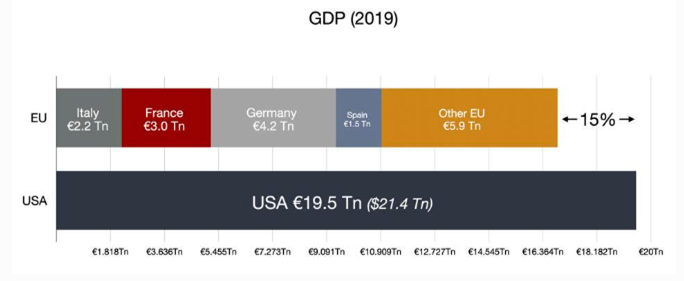

The EU’s control over the material, institutional, and ideational structures in third countries and power over them[5] stems mainly from its economic powerhouse capacity inseparably linked with the reputed economic resilience that has come under fire after the war in Ukraine began. After the eighth package of sanctions against Russia, the European Central Bank[6], which has been more optimistic than most of the private sector counterparts for a long time, forecasted a sharp decline of the Eurozone GDP in the last quarter of this year and the first quarter of next year. The S&P Global Eurozone Manufacturing PMI fell to 48.4 in September from 49.6 in August[7], signalling a further worsening of operating conditions for euro area goods producers. Furthermore, many analysts attribute the euro’s slide to expectations for rapid interest rate increases of the U.S. Federal Reserve to combat inflation at close to 40-year highs. The Deutsche Bank predicts a cut to 0.95-0.97 dollar worth[8], which would correspond to the extreme values of exchange rates since the end of Bretton Woods in 1971. The fall of the euro makes the inflation problem more difficult due to imported inflation. Namely, about half of imported goods in the Eurozone are invoiced in dollars (more euros are needed to pay for imported goods), and slightly less than 40% in euros.[9] Not to mention Germany’s first trade deficit, a unique export-oriented economy in entire Europe, since before the dissolution of Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. The war in Ukraine thus upended the European economy with economic reverberations felt worldwide and exposed significant room for improving the EU’s economic resilience.

Battered by the pandemic and Brexit, current energy prices, and especially disrupted trade relations after the war in Ukraine, the EU might be on the brink of a “Hamiltonian moment” to pursue deeper fiscal integration to support economic resilience. Today, US Treasury is the most liquid financial market in the world, enabling the situation in which US economic competitors are willing to hold their debt, sustaining the dollar as the global reserve currency, and preserving American financial hegemony. Only by creating a federal treasury of its own, the EU could complement its common currency and enter the ring with heavyweight category economic players on an equal footing. The fiscal integration, or in other words, debt mutualisation and launch of Eurobond of sorts, would allow more safety and support EU governments’ borrowing needs. Simultaneously, it would increase pools of investable capital and, most notably, the share of the Euro in global foreign exchange reserves. Just compare the EU sovereign debt market with the U.S. Treasury market relative to GDP.

That is where Europe lags[10], which leaves the EU with inadequate funding to invest in public goods, including defence and security, and its member states without a safety net in terms of available resources in cases of recession and crises. Remember Greece in 2009? All in all, the European policymakers should sooner rather than later get into the swing of deeper fiscal integration and continue with the baby steps they have taken with the fiscal relief brought by the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) to tackle economic resilience deficiencies that worldwide disruptions to trade and investment exposed after the war in Ukraine began.

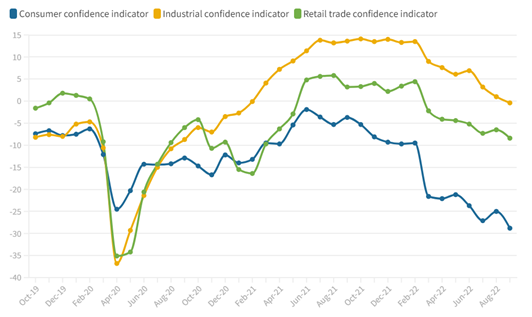

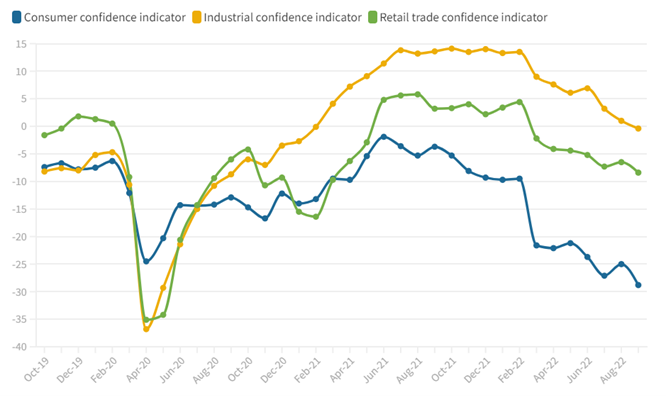

The current gas and electricity prices increased fourfold, or even fivefold, compared with the usual rates, threatening the viability of the EU economy at large and putting at risk the survival of companies that are the backbone of the EU’s value chains. As there is currently no fast alternative to Russian gas besides demand reduction, sustained higher input costs will make European goods less competitive than North American or Asian equivalents. Thus, there is a risk that global supply chains might begin to reorient, moving towards non-European sources. As of August, industrial production had not started to decline, but the shock can be seen propagating through the economy in the form of lower orders, collapsing business and consumer confidence, and lower retail sales.[11] Not to mention inflationary shocks that have been unleashed upon end users. The ETUC European trade union group said wages adjusted for inflation have fallen in every EU member state this year by as much as 9%. The energy crisis is ripping deep into the fabric of European society.

Different actors suggest different approaches to alleviate the energy crisis, and arguably unpleasant trade-offs are to be made. The demand reduction plan[12] was off to a good start. Still, a further effort in that direction may only serve as an addition to an actual solution – as even European Commission head of unit at the energy directorate Monika Zsigri warned.[13] A part of the “actual” solution might lie in electricity coming from renewables. However, the EU must ensure that part of the excess revenue of the renewable energy sector gets redistributed to consumers and disregard expected warnings of the industry representatives about the ripple effect of the EU profit cap. As for the other part of the solution, the EU’s Energy Purchase Platform[14] is an excellent effort and should be implemented without delay. Unlike price caps, which never seem to strike the right balance and may provoke a complete energy supply chain disruption, the Platform would allow the EU to retain the reputation of a market player and substantially increase its negotiation power through pooled demand and enhanced coordination. Finally, the potential of green hydrogen fuel needs to be further assessed. The EU seems to be going in the right direction as regards most of here proposed measures but needs to speed up the decision-making process and concretise its efforts.

The war in Ukraine exposed and dramatized European frailties in several fields, mainly those that apply to the Geopolitics and Economy clusters of Strategic Autonomy, and illuminated the need for an apt balance between diplomatic and hard-power instruments, deeper fiscal integration, and energy autarky. Going down that road is easier said than done. Still, the political will seems to exist when looking at the conclusions of the European Council’s Versailles Declaration of 11 March 2022.[15] However, to achieve that end goal and pursue the above-described roadmap, EU member states need to end its strategic cacophony and start being efficient in pursuit of the EU-SA. Otherwise, the global turmoil might push the EU into the geopolitical backwater.

The following two parts of the blog series will explore the partnership with the US and study the relationship with other geopolitical competitors, respectively, in the context of opportunities for achieving deeper EU-SA.

[1] See more at: https://carnegieeurope.eu/2021/03/08/eu-s-strategic-autonomy-trap-pub-83955.

[2] Allan Duncan, ‘The Minsk Conundrum: Western Policy and Russia’s War in Eastern Ukraine’, Chatham House, 22 May 2020, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2020-05-22-minsk-conundrum-allan.pdf.

[3] ‘Macron Vows “de-Escalation,” but Hints at Concessions to Putin’, POLITICO, 6 February 2022, https://www.politico.eu/article/emmanuel-macron-vows-for-de-escalation-and-dialogue-ahead-of-russian-trip-putin-ukraine/.

[4] Eugene Chausovsky, ‘Why Mediation Around Ukraine Keeps Failing’, Foreign Policy (blog), accessed 7 November 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/02/10/mediation-ukraine-russia-2014-war-west/.

[5] For clarification, see more about analytically eclectic notion of transnational power over (TNPO).

[6] See more at: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/projections/html/ecb.projections202209_ecbstaff~3eafaaee1a.en.html.

[7] See more at: https://www.pmi.spglobal.com/Public/Home/PressRelease/7f7c7616023b42029707537a14443b78.

[8] Elliot Smith, ‘Euro Continues to Slide toward Dollar Parity — and Could Fall Even Further’, CNBC, accessed 17 November 2022, https://www.cnbc.com/2022/07/07/euro-continues-to-slide-toward-dollar-parity-and-could-fall-even-further.html.

[9] See more at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=International_trade_in_goods_by_invoicing_currency.

[10] George Calhoun, ‘Europe’s Hamiltonian Moment – What Is It Really?’, Forbes, accessed 16 November 2022, https://www.forbes.com/sites/georgecalhoun/2020/05/26/europes-hamiltonian-moment–what-is-it-really/

[11] Zsolt Darvas et al., ‘How European Union Energy Policies Could Mitigate the Coming Recession’, Bruegel | The Brussels-based economic think tank, accessed 16 November 2022, https://www.bruegel.org/blog-post/how-european-union-energy-policies-could-mitigate-coming-recession-0.

[12] See more at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_4608.

[13] See more at: https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/natural-gas/092122-gas-demand-reduction-key-for-upcoming-winter-but-situation-manageable-ec

[14] See more at: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-security/eu-energy-platform_en

[15] See more at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/54773/20220311-versailles-declaration-en.pdf.

Reference[+]

| ↑1 | See more at: https://carnegieeurope.eu/2021/03/08/eu-s-strategic-autonomy-trap-pub-83955. |

|---|