Headquarters: Svetog Nauma 7, 11000

Office address: Đorđa Vajferta 13, 11000

Phone:: +381 11 4529 323

The public administration reform process in Serbia, albeit a necessary step for establishing a more modern and citizen-oriented administration, has brought its share of obstacles for civil servants working in public administration (PA) bodies. The process of rationalisation, lower wages, and other measures have changed the work conditions for civil servants, especially because these changes were complemented by fluctuation in political staff and a negative portrayal of civil servants in the media and the wider public. Unlike some European countries, the United Kingdom for example, where civil service affiliation brings a rather reputable position and social status, and where the trust in civil servants is increasing,[1] the current image of Serbia’s PA and its civil servants requires major changes.

During our most recent research project on human resource management in the PA, both former and current civil servants indicated that frequent political changes have resulted in professional civil servants being used as scapegoats. As an outcome of this process, these state employees have found themselves in a disadvantageous position – they have had to handle a lack of political support on one hand, and a negative image of their profession in the wider public on the other. While our research focuses on civil servants working on jobs related to the EU integration process (including the management of EU and other development funds), these results can be used as indicative of a wider dissatisfaction of staff within the PA.

How does the wider public picture civil servants? The common characterisation is that of civil servants as protected from sanctions, lazy, underperforming, disinterested in their work, etc. An illustration could be the pejorative phrase “protected as a polar bear”, widely present in public discourse to describe a civil servant who has all the legal means to remain safe at his or her workplace, despite their actual performance. Additionally, this characterisation is not limited to the private sphere, but is relatively widely spread in the media as well. For an example, one of the larger media outlets titled one of their articles “Malady of Civil Servants: Don’t bother me, I’m sleeping at work.”[2] Another example of the common understanding of the public administration and wider public sector in Serbia is a popular TV comedy “Government Job”, focusing on three incompetent local servants who aimlessly spend their working hours.

While it is true that the legal framework makes it difficult to sanction or terminate the employment of civil servants, and that this situation allows unqualified individuals to remain in their positions, our recent research insights offer a another perspective of this group of public sector employees. Namely, the process of rationalisation has left the Serbian PA with a lower number of civil servants than the average EU member state administration.[3] This creates a situation in which problems such as unpaid overtime, work pressure, understaffed units, unattainable deadlines, difficulties for managers to motivate and manage their staff, and others issues abound and prevent civil servants from performing to their fullest potential. Consequently, the adequate performance management in the organisation is lacking, in the stressful environment in which ad hoc tasks are emerging constantly, prioritisation is hampered while responsibilities are not distributed properly among the employees. In particular, this also means that instead of innovating and reforming the PA, civil servants may often be ‘stuck’ with repetitive administrative tasks which have no added value for the work of the administration.

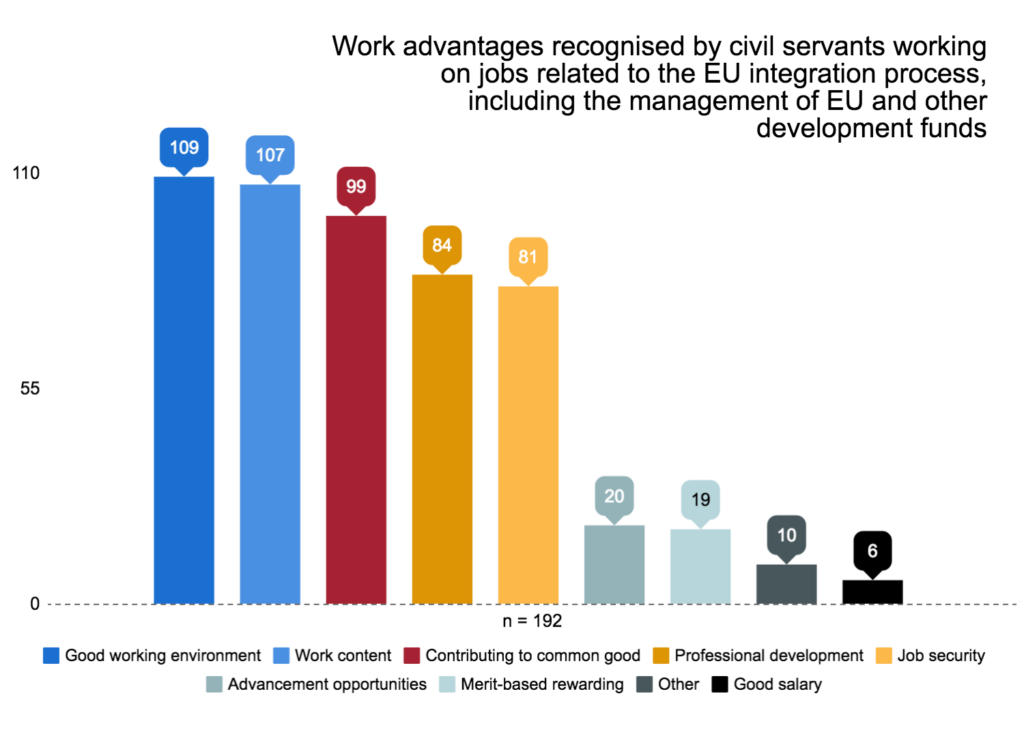

An additionally relevant insight from our research has been the value which civil servants give to the nature of their work. More precisely, work content and the feeling of contributing to the common good are among the three job advantages indicated by civil servants. This is an important result, given that it confirms the theoretical assumption about two types of work motivations, materialistic and nonmaterialistic. As a UNDP report from 2010 explains:

Non‐materialistic motivation is particularly strong in the public sector, and so‐called “public service motivation” may be defined as an altruistic motivation to serve the interests of the community.[4]

If you want to keep reading about civil servants in the context of Serbia’s EU accession and the need to retain quality staff, go to our policy study Towards a Smart Staff Retention Policy for the Sustainable EU Integration of Serbia. This study was produced within the German-Serbian development cooperation programme Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH and the project “Support to EU Accession Negotiations in Serbia.” Additional financial support was provided by the Social Inclusion and Poverty Reduction Unit of the Government of the Republic of Serbia (SIPRU).In this context, our research reveals that the insufficient recognition of the importance of the work of civil servants presents an obstacle for motivating them and fostering an innovative and result-oriented atmosphere within the PA. The degraded image of the civil servant in the media and the wider public, combined with the lack of appreciation from the political leadership, threatens to influence the decision of qualified civil servants to leave the administration. From a more long-term perspective for Serbia, a quality PA reform and a successful EU integration process are impossible without adequately motivated civil servants who present the backbone of these processes. Additionally, a negative image of civil servants will continue to create distrust in the PA and the public sector in general. Hence, choosing not to invest in ameliorating the image of the public administration is a risk both for strategic political goals of Serbia, as well as for the long-term relationship between the public sector and the citizens it is supposed to serve.

[1] Ipsos MORI, “Politicians are still trusted less than estate agents, journalists and bankers,” Public Sector News, 22 January 2016,

https://www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori/en-uk/politicians-are-still-trusted-less-estate-agents-journalists-and-bankers.

[2] Blic, “Boljka državnih službenika: Ne ometaj, spavam na poslu,” 14 December, 2014,

http://www.blic.rs/vesti/drustvo/boljka-drzavnih-sluzbenika-ne-ometaj-spavam-na-poslu/9rr73gw.

[3] Ministry of Public Administration and Local Self-Government, “Modern State – Rational State: How much, how, and why?”, position paper, Belgrade, May 2015, http://www.mduls.gov.rs/doc/Pozicioni%20dokument_Moderna%20i%20racionalna%20drzava.docx.

[4] UNDP, Motivating Civil Servants for Reform and Performance, 2010, http://orbi.ulg.be/bitstream/2268/37467/1/Motivating%20Civil%20Servants%20for%20Reform%20and%20Performance.pdf.